Something published a few days ago in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette seemed worth sharing. Here's a few points from Jack Kelly's March 22 article, "O-bailout and AIG":

- The Obama administration knew about the controversial $165 million in bonuses paid out by AIG several months before the public outrage regarding the bonuses occurred

- Some commentators suspect the administration feigned surprise and a sudden burst of outrage regarding the bonuses to seem "onside" with the public. The administration also chose to focus public attention on the $165 million in bonuses in order to divert attention away from how the $180 billion they gave AIG was spent.

- How was the $180 million spent? Well, AIG had to make payments to creditors such as Goldman Sachs, CitiGroup, and JP Morgan Chase. Each of these companies contributed significantly to the Obama campaign: Goldman Sachs, $955, 473; CitiGroup, $653,468; JP Morgan Chase (whose founder, J.P. Morgan, made his first profits selling defective rifles to the U.S. Army during the Civil War) contributed $485,823.

- The conclusion you might draw from all this? The patronage system of North American politics continues, and the bailout is another manoeuver to take care of the elite monied caste of our society.

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

Friday, February 6, 2009

Ozymandias: All Good Things Must Come to an End!

Spoiler alert: if you haven't finished reading Watchmen and don't want to know the ending of the forthcoming movie, don't read this!*************************************************

When I teach students about the graphic novel Watchmen, we usually talk about the significance of the name Ozymandias and the Percy Bysshe Shelley poem of the same name (find it online here: http://www.bartleby.com/106/246.html).

Let me quote the relevant part of Shelley's"Ozymandia." In the poem, a traveller explains that he once saw a statue of Ramses II (who was also known as Ozymandias).

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings,

Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!

Although these lines suggest that Ozymandias had achieved something great and long-lasting during his reign ("look on my works"), the traveller of the poem explains that nothing remains alongside the decaying bust, but "the lone and level sands."

The inference to be drawn from the poem is that Ozymandias believed he had built a enduring kingdom, a legacy that would outlive him. However, Ozy's achievements are impermanent - the decaying statue and barren sands stand in contrast to Ozy's claims to lasting greatness. His reign and achievements are temporary, transient, ephemeral.

Ozy's hubris in the poem mirrors that of the similarly-named character in Watchmen. Adrian Veidt (AKA "Ozymandias") assumes that, by staging a fake alien attack, he has compelled the nations of the world to forge a lasting piece - a testament to Veidt's genius and benevolence. However, when the discovery of Rorschach's journal (which contains the truth about the staged alien attack) is foreshadowed at the end of the novel, it's implied that Veidt's triumph (like the real Ozymandias') will be short-lived.

***************

Now, a group of students may not make all those connections themselves; they need to be unpacked through discussion. Accordingly, I usually provide a bit of background on Ramses II, then pose the following questions:

- What "works" do the words on the pedestal refer to?

- How does Ozymandias feel about his "works"?

- How does the area around the statue look?

- Why does the traveller point out that the status is "decaying" and that "nothing beside remains"?

- What is Adrian Veidt's goal in the novel? What similar goals does he and Shelley's Ozymandias have in common?

- What happened to Ozymandias' "works" in the poem? What might happen to Adrian Veidt's "works" or achievements in the novel? What evidence do you have to support your answer?

When I teach students about the graphic novel Watchmen, we usually talk about the significance of the name Ozymandias and the Percy Bysshe Shelley poem of the same name (find it online here: http://www.bartleby.com/106/246.html).

Let me quote the relevant part of Shelley's"Ozymandia." In the poem, a traveller explains that he once saw a statue of Ramses II (who was also known as Ozymandias).

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings,

Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!

Although these lines suggest that Ozymandias had achieved something great and long-lasting during his reign ("look on my works"), the traveller of the poem explains that nothing remains alongside the decaying bust, but "the lone and level sands."

The inference to be drawn from the poem is that Ozymandias believed he had built a enduring kingdom, a legacy that would outlive him. However, Ozy's achievements are impermanent - the decaying statue and barren sands stand in contrast to Ozy's claims to lasting greatness. His reign and achievements are temporary, transient, ephemeral.

Ozy's hubris in the poem mirrors that of the similarly-named character in Watchmen. Adrian Veidt (AKA "Ozymandias") assumes that, by staging a fake alien attack, he has compelled the nations of the world to forge a lasting piece - a testament to Veidt's genius and benevolence. However, when the discovery of Rorschach's journal (which contains the truth about the staged alien attack) is foreshadowed at the end of the novel, it's implied that Veidt's triumph (like the real Ozymandias') will be short-lived.

***************

Now, a group of students may not make all those connections themselves; they need to be unpacked through discussion. Accordingly, I usually provide a bit of background on Ramses II, then pose the following questions:

- What "works" do the words on the pedestal refer to?

- How does Ozymandias feel about his "works"?

- How does the area around the statue look?

- Why does the traveller point out that the status is "decaying" and that "nothing beside remains"?

- What is Adrian Veidt's goal in the novel? What similar goals does he and Shelley's Ozymandias have in common?

- What happened to Ozymandias' "works" in the poem? What might happen to Adrian Veidt's "works" or achievements in the novel? What evidence do you have to support your answer?

Tuesday, December 30, 2008

Myths Make Me Madoff

This post’s pithy aphorism comes from Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, although I found it second-hand in Anton Chekhov's short story “Gooseberries”:

The falsehood that exalts we cherish more

Than meaner truths that are a thousand strong.

Chekhov’s story “Gooseberries” tells the story of a man who toils his entire life to purchase a plot of land and chew idly upon berries all day, in imitation of the landed gentry of 19th-century Russia. Once the man, Nikolay, acquires the land and finally has bushels of his longed-for gooseberries, his brother Ivan discovers that the gooseberries are actually quite hard and sour.

This realization leads Ivan to cite the aforementioned Pushkin verse, and the bitter gooseberries become a symbol for all the pleasant myths we use to cover up the unpleasant bits of our society. Some such myths that come to mind at the present moment are (for example) that the economic market will correct itself – albeit after life-upending turbulence – and that mysterious, intangible “market forces” are to blame for financial crises like the one many of us are currently experiencing, rather than the rabid greed most recently exemplified by Bernie Madoff.

The falsehood that exalts we cherish more

Than meaner truths that are a thousand strong.

Chekhov’s story “Gooseberries” tells the story of a man who toils his entire life to purchase a plot of land and chew idly upon berries all day, in imitation of the landed gentry of 19th-century Russia. Once the man, Nikolay, acquires the land and finally has bushels of his longed-for gooseberries, his brother Ivan discovers that the gooseberries are actually quite hard and sour.

This realization leads Ivan to cite the aforementioned Pushkin verse, and the bitter gooseberries become a symbol for all the pleasant myths we use to cover up the unpleasant bits of our society. Some such myths that come to mind at the present moment are (for example) that the economic market will correct itself – albeit after life-upending turbulence – and that mysterious, intangible “market forces” are to blame for financial crises like the one many of us are currently experiencing, rather than the rabid greed most recently exemplified by Bernie Madoff.

Sunday, October 12, 2008

Is Google Making Us Stoopid?

Perhaps those who dismiss critics of the Internet as Luddites or nostalgists will be proved correct, and from our hyperactive, data-stoked minds will spring a golden age of intellectual discovery and universal wisdom. Then again, the Net isn’t the alphabet, and although it may replace the printing press, it produces something altogether different. The kind of deep reading that a sequence of printed pages promotes is valuable not just for the knowledge we acquire from the author’s words but for the intellectual vibrations those words set off within our own minds. In the quiet spaces opened up by the sustained, undistracted reading of a book, or by any other act of contemplation, for that matter, we make our own associations, draw our own inferences and analogies, foster our own ideas. Deep reading, as Maryanne Wolf argues, is indistinguishable from deep thinking.

- Nicholas Carr, “Is Google Making Us Stoopid,” The Atlantic July/August 2008

The gist of Carr's article is this: when powerful tools like the internet make lots of information instantly available, there is pressure put upon people to process information more quickly. However, processing more information can be achieved only through taking more time or processing information on a shallower, more superficial level. That is to say that, when confronted with more information, a person will be compelled to merely comprehend it, as opposed to analyzing or evaluating it. With Google and other tools shovelling sites and blogs and streaming video our way, we may have more information, but we do less with it. Conversely, if you agree with Carr's argument, spending time with a single article or book and reading it slowly and thoroughly allows you to enter into a conversation with that material. By the end of your reading (and re-reading), you have developed some thoughts of your own, rather than simply comsuming the thoughts of the author.

- Nicholas Carr, “Is Google Making Us Stoopid,” The Atlantic July/August 2008

The gist of Carr's article is this: when powerful tools like the internet make lots of information instantly available, there is pressure put upon people to process information more quickly. However, processing more information can be achieved only through taking more time or processing information on a shallower, more superficial level. That is to say that, when confronted with more information, a person will be compelled to merely comprehend it, as opposed to analyzing or evaluating it. With Google and other tools shovelling sites and blogs and streaming video our way, we may have more information, but we do less with it. Conversely, if you agree with Carr's argument, spending time with a single article or book and reading it slowly and thoroughly allows you to enter into a conversation with that material. By the end of your reading (and re-reading), you have developed some thoughts of your own, rather than simply comsuming the thoughts of the author.

Sunday, February 3, 2008

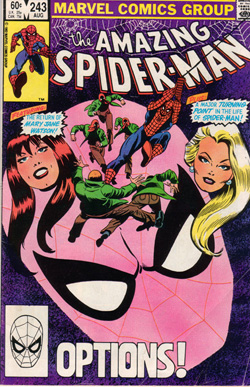

A Hero for the Neurotic in All of Us

Peter Parker, like most of us, swings moods more often than he swings webs. He is the neurotic in all of us, without the caricature of neurosis that allows us to laugh unselfconsciously at Woody Allen and George Costanza. Like most of us, Peter worries about paying the rent, about getting the girl, and about the acuity of his moral sense: does he do good for its own sake, or to buoy his own sense of self-worth?

Peter Parker, like most of us, swings moods more often than he swings webs. He is the neurotic in all of us, without the caricature of neurosis that allows us to laugh unselfconsciously at Woody Allen and George Costanza. Like most of us, Peter worries about paying the rent, about getting the girl, and about the acuity of his moral sense: does he do good for its own sake, or to buoy his own sense of self-worth?Pete’s neuroses sometimes get the better of him; at certain moments of his career, they have crippled him physically, robbing him of his ability to stick to walls and lift car-weight loads over his head. But he always returns to the antidote of humour: he can make a crack about Doc Ock’s bowl-cut at the same time he’s stopping the villain from destroying New York City. In the darkest moments, he lightens the mood by sheer force of will. Peter’s ability to overcome the big and little troubles of life makes him heroic, in a way that makes the “super” prefix almost superfluous.

(Note: I wrote up this meditation on Spider-Man for submission to the "In Character" blog on NPR.com. It doesn't include a direct quotation as these entries normally do, and so I hope you'll forgive me for this rare contravention of the blog rules.)

Friday, February 1, 2008

Blindness

"Fighting has always been, more or less, a form of blindness."

- Jose Saramago, in the novel Blindness (1995)

This quotation comes from the novel Blindness, in which people across an unidentified country fall victim to an infection that robs them of their sight (they see instead a milky whiteness before them at all times). Saramago seems to be saying that we can only direct aggression at another person once we stop perceiving his or her complexity and perceive only that which frustrates our own self-centred needs. In this sense, then, the opposite of fighting is careful consideration of other people's needs and an ability to envision compromises.

Don't be blind!

- Jose Saramago, in the novel Blindness (1995)

This quotation comes from the novel Blindness, in which people across an unidentified country fall victim to an infection that robs them of their sight (they see instead a milky whiteness before them at all times). Saramago seems to be saying that we can only direct aggression at another person once we stop perceiving his or her complexity and perceive only that which frustrates our own self-centred needs. In this sense, then, the opposite of fighting is careful consideration of other people's needs and an ability to envision compromises.

Don't be blind!

Monday, August 13, 2007

The Dangers of Austerity

William Butler Yeats writes lines of such elegance and spiritual force that I find they resonate with me, like an unsettling, too-truthful dream, until I find an outlet for them. And thus the following quote:

Too long a sacrifice can make a stone of the heart.

(W.B. Yeats, "Easter 1916)

Yeats wrote this in reference to the sacrifices of the Irish nationalist movement, which sought to win Ireland's freedom from the United Kingdom into which it had forcefully been drawn in the early 1800s (and, of course, Ireland had been ruled by the English to various degrees since the 1300s). Irish nationalist movements had flared up occasionally throughout the centuries of English colonial rule, only to be snuffed out by the greater military resources of the English.

The armed rising that took place on Easter 1916 was the latest act of resistance plotted by Irish nationalists. They took over the post office in the center of Dublin and used it as a military base for the Easter Rising. The English sent battleships into the city centre, and waited out the leaders of the rising, executing all of them (save one) by firing squad. The death of these men was only the latest of many "sacrifices" incurred by Irish patriots.

In the poem, then, Yeats is suggesting that resisting the English may have too grave a cost - the drawn out resistance to English rule and the deaths that resulted threatened to make the Irish a cold and embittered people.

Yet, while the poem addresses a very specific sacrifice, Yeats' line has a lot of truth regarding sacrifices in general. We often make personal sacrifices so that we might come closer to realizing our goals - we avoid eating out or going on vacation to save for a car, a house, etc; we sacrifice time with loved ones to study or work; we forego new relationships to avoid being hurt. But that sustained act of self-denial can have a deadening effect upon us: repeatedly denying ourselves of the things that bring us joy eventually begins to erode our capacity to feel joy. At least this is what Yeats would have us believe when he speaks of a heart turned to stone, and I have found that he's usually worth listening to...

Too long a sacrifice can make a stone of the heart.

(W.B. Yeats, "Easter 1916)

Yeats wrote this in reference to the sacrifices of the Irish nationalist movement, which sought to win Ireland's freedom from the United Kingdom into which it had forcefully been drawn in the early 1800s (and, of course, Ireland had been ruled by the English to various degrees since the 1300s). Irish nationalist movements had flared up occasionally throughout the centuries of English colonial rule, only to be snuffed out by the greater military resources of the English.

The armed rising that took place on Easter 1916 was the latest act of resistance plotted by Irish nationalists. They took over the post office in the center of Dublin and used it as a military base for the Easter Rising. The English sent battleships into the city centre, and waited out the leaders of the rising, executing all of them (save one) by firing squad. The death of these men was only the latest of many "sacrifices" incurred by Irish patriots.

In the poem, then, Yeats is suggesting that resisting the English may have too grave a cost - the drawn out resistance to English rule and the deaths that resulted threatened to make the Irish a cold and embittered people.

Yet, while the poem addresses a very specific sacrifice, Yeats' line has a lot of truth regarding sacrifices in general. We often make personal sacrifices so that we might come closer to realizing our goals - we avoid eating out or going on vacation to save for a car, a house, etc; we sacrifice time with loved ones to study or work; we forego new relationships to avoid being hurt. But that sustained act of self-denial can have a deadening effect upon us: repeatedly denying ourselves of the things that bring us joy eventually begins to erode our capacity to feel joy. At least this is what Yeats would have us believe when he speaks of a heart turned to stone, and I have found that he's usually worth listening to...

Will Not Compute

...friends, every day do something that won't compute.

- Wendell Berry

The poem from which this line is taken is about living your life in a way other than that prescribed by bureaucracy and business interests. The line asks us to do things that don't seem "normal" and which may confuse anyone who lives their life according to "common sense." Why challenge or resist common sense? Well, because common sense is just that - a system of beliefs and ideas that are held by the majority of the people around you. To live your life according to the precepts of the majority means that you trust VERY STRONGLY that the majority of people in your town or city know exactly what they're doing. That's probably not very likely.

Especially because the majority of people around you aren't operating solely on what they have figured out for themselves or as a community. No, much "common sense" is also a product of the suggestions and images we receive from the government, media, schools, business, and various other institutions with interests they hope to promote by cultivating particular germs in the larger store of "common sense." French critics have a more precise term for this kind of common sense - idees recue (received ideas). Received ideas are those notions that have filtered out into society and are accepted as valid simply because they are repeatedly stated. "Green consumerism" is an idea that has enjoyed a good deal of uncritical reception, for example, but which holds some problems upon closer examination (i.e. that often the "greenest" thing you can do is curb your consumption).

How to avoid the pitfalls of common sense and received ideas? Take actions and think thoughts that "don't compute" in the network of common sense. The poet from whom I took the quote suggests doing things like "planting sequoias" and "asking questions that have no answers."

For my part, yesterday I bought the ingredients to make bread and waited 18 hours for it to rise, when I could've just bought a loaf for $1.50. But can you really put a price on the satisfaction that comes with making your own ball of baked dough?

*******

Excerpt from Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front

By Wendell Berry

Love the quick profit, the annual raise,

vacation with pay. Want more

of everything ready-made. Be afraid

to know your neighbors and to die.

And you will have a window in your head.

Not even your future will be a mystery

any more. Your mind will be punched in a card

and shut away in a little drawer.

When they want you to buy something

they will call you. When they want you

to die for profit they will let you know.

So, friends, every day do something

that won't compute. Love the lord.

Love the world. Work for nothing.

Take all that you have and be poor.

Love someone who does not deserve it.

Denounce the government and embrace

the flag.

- Wendell Berry

The poem from which this line is taken is about living your life in a way other than that prescribed by bureaucracy and business interests. The line asks us to do things that don't seem "normal" and which may confuse anyone who lives their life according to "common sense." Why challenge or resist common sense? Well, because common sense is just that - a system of beliefs and ideas that are held by the majority of the people around you. To live your life according to the precepts of the majority means that you trust VERY STRONGLY that the majority of people in your town or city know exactly what they're doing. That's probably not very likely.

Especially because the majority of people around you aren't operating solely on what they have figured out for themselves or as a community. No, much "common sense" is also a product of the suggestions and images we receive from the government, media, schools, business, and various other institutions with interests they hope to promote by cultivating particular germs in the larger store of "common sense." French critics have a more precise term for this kind of common sense - idees recue (received ideas). Received ideas are those notions that have filtered out into society and are accepted as valid simply because they are repeatedly stated. "Green consumerism" is an idea that has enjoyed a good deal of uncritical reception, for example, but which holds some problems upon closer examination (i.e. that often the "greenest" thing you can do is curb your consumption).

How to avoid the pitfalls of common sense and received ideas? Take actions and think thoughts that "don't compute" in the network of common sense. The poet from whom I took the quote suggests doing things like "planting sequoias" and "asking questions that have no answers."

For my part, yesterday I bought the ingredients to make bread and waited 18 hours for it to rise, when I could've just bought a loaf for $1.50. But can you really put a price on the satisfaction that comes with making your own ball of baked dough?

*******

Excerpt from Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front

By Wendell Berry

Love the quick profit, the annual raise,

vacation with pay. Want more

of everything ready-made. Be afraid

to know your neighbors and to die.

And you will have a window in your head.

Not even your future will be a mystery

any more. Your mind will be punched in a card

and shut away in a little drawer.

When they want you to buy something

they will call you. When they want you

to die for profit they will let you know.

So, friends, every day do something

that won't compute. Love the lord.

Love the world. Work for nothing.

Take all that you have and be poor.

Love someone who does not deserve it.

Denounce the government and embrace

the flag.

Friday, August 10, 2007

Local Celebrities

The people I loved were celebrities, surrounded by rumor and fanfare; the places I sat with them, movie lots and monuments. No doubt all of this is not true remembrance but the ruinous work of nostalgia, which obliterates the past, and no doubt, as usual, I have exaggerated everything.

- Michael Chabon, in The Mysteries of Pittsburgh

When I lived in Massachusetts, one of my very good friends was a Greek guy by the name of Vasilis. Vasilis is a very charming, polite, witty, and wonderfully controlled personality - he has a habit of saying the right thing at the right time. For example, when I asked him once why he chose to leave a party at 11:30, he responded, in the staccato rhythm required because of his slight discomfort with English, "you should always leave them wanting more." He was not at all egotistical, and that's why I cracked up when he said this.

But from that point on, I started referring to Vasilis as a "local celebrity," and he did the same to me. We were poking fun at each other's actual insignificance; but at the same time, in a tight knit group of a dozen or so friends, it was easy to feel that we all were celebrities, the focus of each other's "rumors and fanfare," the topic of conversations that others reserve for chatting about Hilton and Richie around the water cooler.

The point, of both the quote and my story, is that in the finer moments and finer situations of our lives, it is possible to feel that the people you know are the center of a universe (albeit your own small one), the only people you really need to or care to know.

Postscript: The Mysteries of Pittsburgh is Chabon's first novel and, in reading it, I've decided that he's awesome (he also wrote the screenplay for Spiderman 2). He lived in Pittsburgh for several years, proving again the sheer awesomeness of the 'Burgh.

- Michael Chabon, in The Mysteries of Pittsburgh

When I lived in Massachusetts, one of my very good friends was a Greek guy by the name of Vasilis. Vasilis is a very charming, polite, witty, and wonderfully controlled personality - he has a habit of saying the right thing at the right time. For example, when I asked him once why he chose to leave a party at 11:30, he responded, in the staccato rhythm required because of his slight discomfort with English, "you should always leave them wanting more." He was not at all egotistical, and that's why I cracked up when he said this.

But from that point on, I started referring to Vasilis as a "local celebrity," and he did the same to me. We were poking fun at each other's actual insignificance; but at the same time, in a tight knit group of a dozen or so friends, it was easy to feel that we all were celebrities, the focus of each other's "rumors and fanfare," the topic of conversations that others reserve for chatting about Hilton and Richie around the water cooler.

The point, of both the quote and my story, is that in the finer moments and finer situations of our lives, it is possible to feel that the people you know are the center of a universe (albeit your own small one), the only people you really need to or care to know.

Postscript: The Mysteries of Pittsburgh is Chabon's first novel and, in reading it, I've decided that he's awesome (he also wrote the screenplay for Spiderman 2). He lived in Pittsburgh for several years, proving again the sheer awesomeness of the 'Burgh.

Wednesday, July 11, 2007

Writing is a better way of thinking

Reading maketh a full man, conference a ready man, and writing an exact man.

- Francis Bacon, 16th century English philosopher

Bacon's point here is to say that while reading prodigiously will "fill" you with ideas and information, it is only when you are called upon to discuss those ideas and facts that you really apply them. More than this even, writing forces you to master your thoughts, to organize them and refine them, so as to express them clearly and concisely. It is this process that makes writing enjoyable (at least for me), and gives me a sense of satisfaction, that I have managed to say at least one thing with precision. It is also that wrangling with words, that wrestling which culminates in a satisfying victory, that probably spurred one poet to say

I hate writing, but I love having written.

- Dorothy Parker

- Francis Bacon, 16th century English philosopher

Bacon's point here is to say that while reading prodigiously will "fill" you with ideas and information, it is only when you are called upon to discuss those ideas and facts that you really apply them. More than this even, writing forces you to master your thoughts, to organize them and refine them, so as to express them clearly and concisely. It is this process that makes writing enjoyable (at least for me), and gives me a sense of satisfaction, that I have managed to say at least one thing with precision. It is also that wrangling with words, that wrestling which culminates in a satisfying victory, that probably spurred one poet to say

I hate writing, but I love having written.

- Dorothy Parker

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)