This post’s pithy aphorism comes from Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, although I found it second-hand in Anton Chekhov's short story “Gooseberries”:

The falsehood that exalts we cherish more

Than meaner truths that are a thousand strong.

Chekhov’s story “Gooseberries” tells the story of a man who toils his entire life to purchase a plot of land and chew idly upon berries all day, in imitation of the landed gentry of 19th-century Russia. Once the man, Nikolay, acquires the land and finally has bushels of his longed-for gooseberries, his brother Ivan discovers that the gooseberries are actually quite hard and sour.

This realization leads Ivan to cite the aforementioned Pushkin verse, and the bitter gooseberries become a symbol for all the pleasant myths we use to cover up the unpleasant bits of our society. Some such myths that come to mind at the present moment are (for example) that the economic market will correct itself – albeit after life-upending turbulence – and that mysterious, intangible “market forces” are to blame for financial crises like the one many of us are currently experiencing, rather than the rabid greed most recently exemplified by Bernie Madoff.

Tuesday, December 30, 2008

Sunday, October 12, 2008

Is Google Making Us Stoopid?

Perhaps those who dismiss critics of the Internet as Luddites or nostalgists will be proved correct, and from our hyperactive, data-stoked minds will spring a golden age of intellectual discovery and universal wisdom. Then again, the Net isn’t the alphabet, and although it may replace the printing press, it produces something altogether different. The kind of deep reading that a sequence of printed pages promotes is valuable not just for the knowledge we acquire from the author’s words but for the intellectual vibrations those words set off within our own minds. In the quiet spaces opened up by the sustained, undistracted reading of a book, or by any other act of contemplation, for that matter, we make our own associations, draw our own inferences and analogies, foster our own ideas. Deep reading, as Maryanne Wolf argues, is indistinguishable from deep thinking.

- Nicholas Carr, “Is Google Making Us Stoopid,” The Atlantic July/August 2008

The gist of Carr's article is this: when powerful tools like the internet make lots of information instantly available, there is pressure put upon people to process information more quickly. However, processing more information can be achieved only through taking more time or processing information on a shallower, more superficial level. That is to say that, when confronted with more information, a person will be compelled to merely comprehend it, as opposed to analyzing or evaluating it. With Google and other tools shovelling sites and blogs and streaming video our way, we may have more information, but we do less with it. Conversely, if you agree with Carr's argument, spending time with a single article or book and reading it slowly and thoroughly allows you to enter into a conversation with that material. By the end of your reading (and re-reading), you have developed some thoughts of your own, rather than simply comsuming the thoughts of the author.

- Nicholas Carr, “Is Google Making Us Stoopid,” The Atlantic July/August 2008

The gist of Carr's article is this: when powerful tools like the internet make lots of information instantly available, there is pressure put upon people to process information more quickly. However, processing more information can be achieved only through taking more time or processing information on a shallower, more superficial level. That is to say that, when confronted with more information, a person will be compelled to merely comprehend it, as opposed to analyzing or evaluating it. With Google and other tools shovelling sites and blogs and streaming video our way, we may have more information, but we do less with it. Conversely, if you agree with Carr's argument, spending time with a single article or book and reading it slowly and thoroughly allows you to enter into a conversation with that material. By the end of your reading (and re-reading), you have developed some thoughts of your own, rather than simply comsuming the thoughts of the author.

Sunday, February 3, 2008

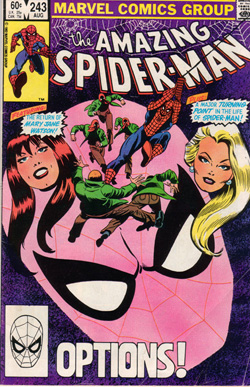

A Hero for the Neurotic in All of Us

Peter Parker, like most of us, swings moods more often than he swings webs. He is the neurotic in all of us, without the caricature of neurosis that allows us to laugh unselfconsciously at Woody Allen and George Costanza. Like most of us, Peter worries about paying the rent, about getting the girl, and about the acuity of his moral sense: does he do good for its own sake, or to buoy his own sense of self-worth?

Peter Parker, like most of us, swings moods more often than he swings webs. He is the neurotic in all of us, without the caricature of neurosis that allows us to laugh unselfconsciously at Woody Allen and George Costanza. Like most of us, Peter worries about paying the rent, about getting the girl, and about the acuity of his moral sense: does he do good for its own sake, or to buoy his own sense of self-worth?Pete’s neuroses sometimes get the better of him; at certain moments of his career, they have crippled him physically, robbing him of his ability to stick to walls and lift car-weight loads over his head. But he always returns to the antidote of humour: he can make a crack about Doc Ock’s bowl-cut at the same time he’s stopping the villain from destroying New York City. In the darkest moments, he lightens the mood by sheer force of will. Peter’s ability to overcome the big and little troubles of life makes him heroic, in a way that makes the “super” prefix almost superfluous.

(Note: I wrote up this meditation on Spider-Man for submission to the "In Character" blog on NPR.com. It doesn't include a direct quotation as these entries normally do, and so I hope you'll forgive me for this rare contravention of the blog rules.)

Friday, February 1, 2008

Blindness

"Fighting has always been, more or less, a form of blindness."

- Jose Saramago, in the novel Blindness (1995)

This quotation comes from the novel Blindness, in which people across an unidentified country fall victim to an infection that robs them of their sight (they see instead a milky whiteness before them at all times). Saramago seems to be saying that we can only direct aggression at another person once we stop perceiving his or her complexity and perceive only that which frustrates our own self-centred needs. In this sense, then, the opposite of fighting is careful consideration of other people's needs and an ability to envision compromises.

Don't be blind!

- Jose Saramago, in the novel Blindness (1995)

This quotation comes from the novel Blindness, in which people across an unidentified country fall victim to an infection that robs them of their sight (they see instead a milky whiteness before them at all times). Saramago seems to be saying that we can only direct aggression at another person once we stop perceiving his or her complexity and perceive only that which frustrates our own self-centred needs. In this sense, then, the opposite of fighting is careful consideration of other people's needs and an ability to envision compromises.

Don't be blind!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)